Beads 33 (2021) O. P.

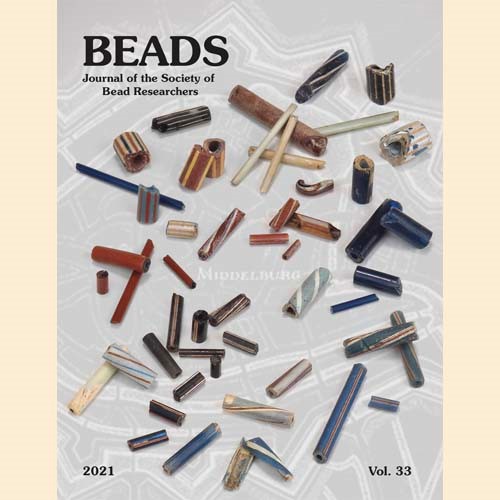

Insight into the 17th-Century Bead Industry of Middelburg, the Netherlands, by Hans van der Storm and Karlis Karklins

During the first half of the 17th century, several beadmaking establishments operated in the city of Middelburg in the southwestern corner of the Netherlands. Bead wasters recovered from several find sites in the old part of the city reveal the diversity of the product line which featured beads decorated with straight and spiral stripes. Several chevron types were also produced. There are similarities with wasters found at contemporary beadmaking sites in Amsterdam, indicating that both production centers made similar bead varieties. Few of the bead varieties represented have correlatives in the areas of North America that were under Dutch control, leaving one guessing what market the Middelburg beads were destined for. In that the city was a major center for the Dutch East India Company, it may be that their market was in that part of the world. Unfortunately, comparative material from South and Southeast Asia is currently lacking.

From Qualitative to Quantitative: Tracking Global Routes and Markets of Venetian Glass Beads during the 18th Century, by Pierre Niccolò Sofia, translated by Brad Loewen

The Venetian glass bead industry has its roots in the Late Middle Ages. The development of Atlantic trade and, particularly, the slave trade from the second half of the 17th century increased the demand for glass beads. The 18th century would be the heyday of this industry, when Venetian beads attained a significant global diffusion. While scholars have long known the global exports of beads from Venice, this paper contributes new quantitative data on their precise routes and markets in the 18th century, toward the Orient and toward the Atlantic. Using beads as a case study, this paper shows how a niche product allowed a Mediterranean city such as Venice to stay connected with the Atlantic world and how the Atlantic slave trade influenced Venetian glass bead exports to the West.

A Beaded Hair Comb of the Early Ming Dynasty, by Valerie Hector

This article describes an unprovenanced artifact: a 700-year-old beaded hair comb probably entombed with a woman who died between 1405 and 1446 during China’s early Ming dynasty. It is intended to establish basic facts and stimulate further research. The comb may be the first intact example of mainland Chinese beadwork to undergo radiocarbon dating as well as laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) analysis. The lead-potash (Pb-K) composition of the comb’s glass coil beads resembles that of coil beads recovered from jar burials of the 15th-17th centuries in Cambodia’s Cardamom Mountains. Thus, the comb links glass coil beads ostensibly made for use within China to coil beads exported to Southeast Asia.

Beadmaking during the 17th and 18th Centuries in Eu County, Normandy, by Guillaume Klaës, translated by Brad Loewen

This paper reconstructs the history of a family of French beadmakers in Eu County, Normandy, from 1687 to 1747, as well as the context of their migration from the urban beadmaking center of Rouen. While Normandy had produced windowpane and bottles since the Middle Ages, artisans who made “crystal” soda glass – the glass of beads – were newcomers from Italy and Languedoc. They founded glassworks in Paris and Rouen in the late 16th century. Conflicts with Rouen artisans and merchants led the Mediterranean glassworkers to migrate to Eu County in 1634, where their crystal factories spun off a rural beadmaking trade. The present research builds on 19th-century archaeological reports of beads and beadmaking wasters in the villages of Aubermesnil-aux-Érables and Villers-sous-Foucarmont. We have identified three generations of the Demary family of beadmakers in the Eu Forest. Using genealogical methods, we have traced their migration from Rouen, their family history, and their links to Mediterranean crystal glassmakers. The example of the Demary patenôtriers sheds light on a transitional period of beadmaking in Normandy, characterized by its ruralization and its proximity with forest glassmaking in the second half of the 17th century.

Glass Beadmaking and Enamel Lampwork in Paris, 1547-1610: Archival and Archaeological Data, by Elise Vanriest, translated by Brad Loewen

This article presents beadmaking in Paris during the second half of the 16th century as seen through period documents and artifacts. Parisian archives document beadmaking by artisans called patenôtriers who made a wide range of glass buttons and jewelry, including beads. Records of the patenôtriers’ guild provide an idea of the number of artisans engaged in this activity, while notarial contracts and estate inventories reveal individual careers and the material dimension of beadmaking in Paris. Patenôtriers obtained their materials – soda glass and enamel supplied as tubes, rods, or ingots – from glassmakers in rural France, Altare in Italy, and a small glassworks that operated in the suburb of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in 1598-1608. They exported rosary beads to Iberia and trade beads to North America. In European terms, Paris was a major beadmaking center during the 16th century and we know its products from a small number of archaeological finds and museum holdings.

A Chemical Comparison of Black Glass Seed Beads from North America and Europe, by Danielle L. Dadiego

Analysis of the elemental composition of glass has gained traction over the past few decades. The growing interest and utilization of non-destructive and micro-destructive analytical techniques has allowed for a more in-depth understanding of glass production, distribution, and consumption. The analysis of glass trade beads in particular has led to the development of a chronological sequencing for non-diagnostic seed beads opacified with metal oxides as well as ore sourcing for cobalt-blue and red beads. There is deficient research on 18th-century glass bead composition, including black manganese-colored beads. This article explores the elemental composition of 162 black seed beads from three 18th-century sites in Pensacola, Florida, and compares the assemblage to a small sample of similar glass beads recovered from three sites in the United States as well as four potential glass production locations in Europe.

The Chemistry of Nueva Cadiz and Associated Beads: Technology and Provenience, by Brad Loewen and Laure Dussubieux

Dating to about 1500-1560, Nueva Cadiz beads are the earliest glass beads found in the Americas, and many questions regarding their technology and provenience surround them. Analysis of 10 beads from the namesake Nueva Cádiz site in Venezuela and 33 beads collected from an unknown site or sites near Tiahuanaco, Bolivia, provide chemical compositions of their turquoise, dark blue, white, red, and colorless glasses. We analyze the sand, flux, and colorants that went into their fabrication. The two collections show a common beadmaking tradition and provenience, except for three beads made of high-lime low-alkali (HLLA) glass. Colorants and opacifiers are cobalt for blue, a tin-based agent for white, and copper for turquoise and red. Trace elements associated with cobalt indicate a variable source for this colorant. By comparing the layers of composite beads, we discover technological aspects of bead design and workshop organization. To investigate provenience, we compare the levels of key elements with other glasses of proven origin. There are similarities with glasses made in Venice and Antwerp, identifying these places as candidates for the origin of Nueva Cadiz beads.

Nueva Cadiz Beads in the Americas: A Preliminary Compositional Comparison, by Heather Walder, Alicia Hawkins, Brad Loewen, Laure Dussubieux, and Joseph A. Petrus

Nueva Cadiz and associated beads are among the earliest categories of European glass beads found in the Americas. Named after the site in Venezuela where they were first identified, these tubular, square-sectioned beads occur in regions of 16th-century Spanish colonial trade. A similar style occurs around Lake Ontario in northeastern North America in areas of 17th-century Dutch and French colonial trade. We compare the chemical composition of beads from South America and Ontario, Canada, to explore their provenience and technology. Differences in key trace elements (Hf, Zr, Nd) strongly indicate separate sand origins for the two bead groups. Comparison with soda-lime glass made in Venice and Antwerp reveals chemical similarities between the South American beads and Venetian glass, and between the Ontario beads and Antwerp glass. The analysis also sheds light on beadmaking technologies.

The Trade Beads of Fort Rivière Tremblante, a North West Company Post on the Upper Assiniboine, Saskatchewan, by Karlis Karklins

The archaeological investigation of Fort Rivière Tremblante, a North West Company post that operated from 1791 to 1798 in what is now southeastern Saskatchewan, Canada, yielded 20,119 glass beads representing 63 varieties, as well as seven wampum. While the bulk of the collection is composed of drawn seed beads, it also contains an exceptional variety of fancy wound beads. A comparison with bead assemblages recovered from other contemporary fur trade sites in western Canada reveals that both the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company carried much the same bead inventory in the region around the turn of the 19th century, with slight variations to accommodate local tastes

Book Review in Volume 33

The Art of Recycled Glass Beads, by Philippe J. Kradolfer and Nomoda E. Djaba, reviewed by Floor Kaspers.